Want to be a Christian intellectual?

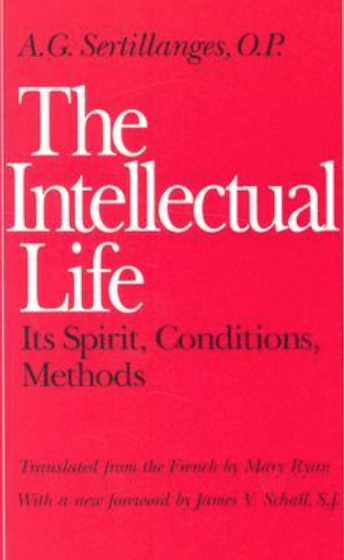

Read The Intellectual Life.

“Let us not be like those people who always seem to be pallbearers at the funeral of the past. Let us utilize, by living, the qualities of the dead” (15).

A man who writes such lines must be read! A. G. Sertillanges’ The Intellectual Life is a necessary agent toward molding Christian thinkers. His opening chapter marks the initial salvo in the battle for “The Intellectual Vocation.” These pages are choice, conditioning Christian minds to consider the importance of study, pursuit of scholarship, and the practicality of everyday living as an intellectual.

A man who writes such lines must be read! A. G. Sertillanges’ The Intellectual Life is a necessary agent toward molding Christian thinkers. His opening chapter marks the initial salvo in the battle for “The Intellectual Vocation.” These pages are choice, conditioning Christian minds to consider the importance of study, pursuit of scholarship, and the practicality of everyday living as an intellectual.

Sertillanges was a French scholar of the Dominican Order(1863-1948). The Intellectual Life was first published in 1921 and has been used in a multiplicity of contexts from seminaries to military academies. James V. Schall, whose foreword opens the volume, encourages every serious thinker to adopt Sertillanges’ intellectual practices. “Practice” is indeed the central premise of the book. Many tomes have been written on the pursuit of knowledge but only this one has been given to the practical outworking of how to practice the craft of being a public intellectual.

Sertillanges was a French scholar of the Dominican Order(1863-1948). The Intellectual Life was first published in 1921 and has been used in a multiplicity of contexts from seminaries to military academies. James V. Schall, whose foreword opens the volume, encourages every serious thinker to adopt Sertillanges’ intellectual practices. “Practice” is indeed the central premise of the book. Many tomes have been written on the pursuit of knowledge but only this one has been given to the practical outworking of how to practice the craft of being a public intellectual.

The opening chapter references work of the mind as a “vocation,” a “calling,” a serious, important pursuit.“Virtue” marks the second chapter, demanding that the scholar recognize The Spirit’s demands on her life. “Organization” and “time” follow in succession safeguarding the necessity of life-space to cultivate, create, and continue the life of the mind. One must know their place in fields of study acknowledging the preeminence of Truth as well as Mystery. “Preparation” is the lengthiest chapter focused on reading, memory, and note-taking. The imperative, arduous nature of writing demands the full attention of the scholar who must communicate her craft to the world. Ultimately, the joyous fruit of one’s labor gives cause to pause, reflecting on the good life of the person who has been gifted to use his intellect for beneficence, toward the betterment of all.

The opening chapter references work of the mind as a “vocation,” a “calling,” a serious, important pursuit.“Virtue” marks the second chapter, demanding that the scholar recognize The Spirit’s demands on her life. “Organization” and “time” follow in succession safeguarding the necessity of life-space to cultivate, create, and continue the life of the mind. One must know their place in fields of study acknowledging the preeminence of Truth as well as Mystery. “Preparation” is the lengthiest chapter focused on reading, memory, and note-taking. The imperative, arduous nature of writing demands the full attention of the scholar who must communicate her craft to the world. Ultimately, the joyous fruit of one’s labor gives cause to pause, reflecting on the good life of the person who has been gifted to use his intellect for beneficence, toward the betterment of all.

Each page contains phrases and paragraphs worthy of memorization. The scholar will be prompted toward both “self-examination” and “pleasure” (4-5). The intellectual vocation is a gift from God requiring “continuity and methodical effort” (3). Discipline and dedication must augment the inherent desires of one called to “this way of life” which must be initiated with “long self-examination” (4). Once The Spirit’s prompting is understood the Christian intellectual is warned “Do not prove faithless to God, to your brethren and to yourself by rejecting a sacred call (5). True intellectual vocation requires “training and tenacity” (4).

Each page contains phrases and paragraphs worthy of memorization. The scholar will be prompted toward both “self-examination” and “pleasure” (4-5). The intellectual vocation is a gift from God requiring “continuity and methodical effort” (3). Discipline and dedication must augment the inherent desires of one called to “this way of life” which must be initiated with “long self-examination” (4). Once The Spirit’s prompting is understood the Christian intellectual is warned “Do not prove faithless to God, to your brethren and to yourself by rejecting a sacred call (5). True intellectual vocation requires “training and tenacity” (4).

Central to Sertillanges’ concern is that the Christian intellectual realize the responsibility of her life. The author asks one long question at the bottom of page eleven direction to the cloistered in their studies. Humility is essential as “the wisdom of the ages” is shared with others (11). Forming “rules of the mind in our present time” directs “men’s hearts toward supreme ends.” Opportunities to allow “the gospel speak out of our lives” (13) providing “life-giving maxims” (15) create a continuous hunger for God-centered knowledge.

Central to Sertillanges’ concern is that the Christian intellectual realize the responsibility of her life. The author asks one long question at the bottom of page eleven direction to the cloistered in their studies. Humility is essential as “the wisdom of the ages” is shared with others (11). Forming “rules of the mind in our present time” directs “men’s hearts toward supreme ends.” Opportunities to allow “the gospel speak out of our lives” (13) providing “life-giving maxims” (15) create a continuous hunger for God-centered knowledge.

But what good is knowledge without discipline? Organization of one’s life is the core of Sertillanges’ writing. Care for the whole person is of first importance (36). Fresh air, exercise, rest, diet, sleep, and self-control are all predominate concerns (37-40). Wives and children are seen as refreshment (41-46), solitude as essential (46-53), and associations (54) as encouragements. Solitude, however, above all else, is essential (55-68). Knowing oneself, the best time of day to think, provides the template for chapter four. Sertillanges reminds this is anything but a selfish pursuit, instead, a necessary, jealous guarding of a thinker’s time “when he really uses it, is in reality charity to all” (99-100).

But what good is knowledge without discipline? Organization of one’s life is the core of Sertillanges’ writing. Care for the whole person is of first importance (36). Fresh air, exercise, rest, diet, sleep, and self-control are all predominate concerns (37-40). Wives and children are seen as refreshment (41-46), solitude as essential (46-53), and associations (54) as encouragements. Solitude, however, above all else, is essential (55-68). Knowing oneself, the best time of day to think, provides the template for chapter four. Sertillanges reminds this is anything but a selfish pursuit, instead, a necessary, jealous guarding of a thinker’s time “when he really uses it, is in reality charity to all” (99-100).

Broadminded study includes the interests of all: “everything is in everything” (102) and “intellectuality admits no compartments” (241). “Synthesis,” “comparison,” “kindred disciplines,” “connections,” and “coherence” suggest the continual need toward interdisciplinarity, the emphasis of chapter five. Focused on one’s specialty alone leaves one alone in his discipline, without light “for its own paths” (102). Better, Sertillanges’ metaphor claims, crops be rotated so as to “not ruin the soil” (104). Yet one discipline must guide all others: theology (109ff). “The unity of faith gives to intellectual work the stamp of a vast cooperation . . . united in God” (110).

Broadminded study includes the interests of all: “everything is in everything” (102) and “intellectuality admits no compartments” (241). “Synthesis,” “comparison,” “kindred disciplines,” “connections,” and “coherence” suggest the continual need toward interdisciplinarity, the emphasis of chapter five. Focused on one’s specialty alone leaves one alone in his discipline, without light “for its own paths” (102). Better, Sertillanges’ metaphor claims, crops be rotated so as to “not ruin the soil” (104). Yet one discipline must guide all others: theology (109ff). “The unity of faith gives to intellectual work the stamp of a vast cooperation . . . united in God” (110).

Sertillanges also allows no division between content and communication, between study and practice. “Reading and study should be spirit and life” (141). Scholars use resources but must not be used by them (154-56). A “banquet of the sages” (158) mandate each intellectual acknowledge how much she owes to others’ past work. Guarding ones’ memory through recollection and reflection is a mandate (181-86). “The expression of thought in words is an act of life” (202). Christian thinkers work “in a spirit of eternity” in the service of Truth (210). Intellectuals are intellectuals “all the time” (216) delighting in the activity of study (220).

Sertillanges also allows no division between content and communication, between study and practice. “Reading and study should be spirit and life” (141). Scholars use resources but must not be used by them (154-56). A “banquet of the sages” (158) mandate each intellectual acknowledge how much she owes to others’ past work. Guarding ones’ memory through recollection and reflection is a mandate (181-86). “The expression of thought in words is an act of life” (202). Christian thinkers work “in a spirit of eternity” in the service of Truth (210). Intellectuals are intellectuals “all the time” (216) delighting in the activity of study (220).

“Try to discern in every occurrence the effort that befits you, the discipline you are capable of, the sacrifice you can make, the subject you can deal with, the thesis you can write, the book that you can read with profit, the public you can serve. Take the measure of all these things humility and confidence. . . . Then throw yourself with your whole heart into your task” (232).

Those who have been given opportunity and privilege of higher education now bear the responsibility of the intellectual vocation. The Christian shows her love for others by using her skills for others’ benefit. Developing intellectual abilities from a decidedly biblical point of view serves others. The Christian intellectual protects his neighbor from unbiblical ideas through identification, analysis, evaluation, and refutation as well as provides his neighbor with biblical ideas for their general wellbeing as a human being. Through all “purity of thought requires purity of soul” (22) mandating that the Christian intellectual benefits his community by committing herself to care of the soul. The practice of intellectual work must have an end toward practice so that the eternal nature of scholarship have immediate, practical application.

Those who have been given opportunity and privilege of higher education now bear the responsibility of the intellectual vocation. The Christian shows her love for others by using her skills for others’ benefit. Developing intellectual abilities from a decidedly biblical point of view serves others. The Christian intellectual protects his neighbor from unbiblical ideas through identification, analysis, evaluation, and refutation as well as provides his neighbor with biblical ideas for their general wellbeing as a human being. Through all “purity of thought requires purity of soul” (22) mandating that the Christian intellectual benefits his community by committing herself to care of the soul. The practice of intellectual work must have an end toward practice so that the eternal nature of scholarship have immediate, practical application.

Review by Mark D. Eckel, President, The Comenius Institute, Indianapolis, IN and Professor of Leadership, Education and Discipleship, Capital Seminary and Graduate School, Washington, D.C. Sertillanges, A.G. The intellectual life: Its spirit, conditions, methods. Translated from the French by Mary Ryan. Foreword by James V. Schall. Reprint, Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press. 1998. 266 pp. $22.95. paper. The review will appear in the 2017 spring issue of the Christian Education Journal.

Review by Mark D. Eckel, President, The Comenius Institute, Indianapolis, IN and Professor of Leadership, Education and Discipleship, Capital Seminary and Graduate School, Washington, D.C. Sertillanges, A.G. The intellectual life: Its spirit, conditions, methods. Translated from the French by Mary Ryan. Foreword by James V. Schall. Reprint, Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press. 1998. 266 pp. $22.95. paper. The review will appear in the 2017 spring issue of the Christian Education Journal.